From the Calypso Deep to the Alps to Galicia and Lebanon, this spring edition of Lapilli explores marine littering, approaches to mitigate climate change beyond reducing greenhouse gas emissions and the forest that supports Venice. This month, we also present two short feature stories from the Magmatic School of Environmental Journalism: on a proposed lithium mine in Extremadura, Spain, and sea level rise in Alexandria, Egypt. As always, we hope you enjoy it; if you do, help us spread the word.

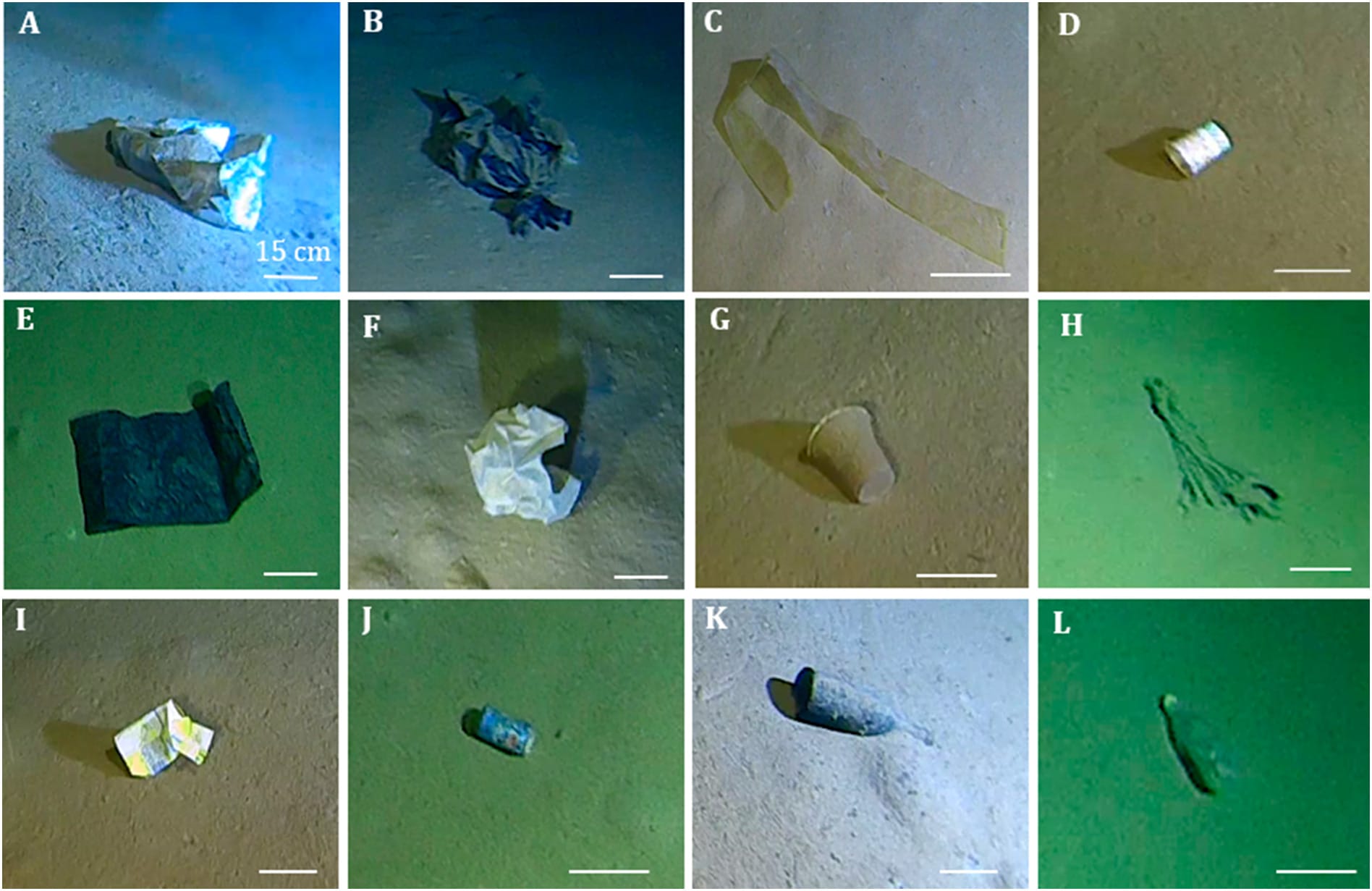

Plastic in the abyss. There’s plastic everywhere — even in the Calypso Deep, the deepest point of the Mediterranean Sea. A research expedition, departing from the southeastern coast of the Peloponnese in the Ionian Sea, used a submarine to reach the seabed at a depth of 5,112 meters (3.17 miles). The mission was led by the University of Barcelona, the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre and the U.S. private company Caladan Oceanic. Their findings paint a troubling picture: a seabed littered with human-made debris, including plastic objects, glass, paper and metal.

According to researchers, lighter materials may have been carried there by ocean currents; however, heavier items are likely the result of people directly dumping at the site for decades — perhaps with the notion that such extreme depths make detection unlikely. The Mediterranean is already known for its vulnerability to pollution from coastal populations, with no shortage of ways for waste to find its way into the sea. In 2021, the Strait of Messina seabed, between Calabria and Sicily, was identified as having the highest density of underwater waste than anywhere else in the world (Oceanographic Magazine).

Fishermen-scientists. Across the Mediterranean, Posidonia oceanica, a vital seagrass species for marine ecosystems, is disappearing. This is partly due to industrial bottom-trawling — an issue that often pits small-scale fishers against larger trawlers, including in the Greek islands. However, a collaboration between England’s University of Plymouth and Greece’s Archipelagos Institute of Marine Conservation has turned to local veteran fishers from the eastern Aegean islands of Fourni, Lipsi, Arki, Patmos and Leros to map the remaining Posidonia meadows.

“The fishermen’s maps show an average accuracy of around 78 percent compared to satellite imagery, with some reaching up to 92 percent!” says the study’s co-author Konstantis Alexopoulos, a researcher at the Archipelagos Institute of Marine Conservation. Coastal fishers' knowledge is often overlooked or dismissed by academic institutions, but this interdisciplinary approach, combined with advanced technology, has led to a more precise understanding of Posidonia’s current state (Kathimerini).

Beside carbon. There is a prevailing tendency to associate environmental disasters with rising temperatures from increased carbon dioxide levels. While it is undeniable that atmospheric carbon dioxide has reached its highest levels in 800,000 years — dramatically disrupting planetary balance — other contributing factors, such as changes in land-use, deserve urgent attention, too.

A report published on Mongabay compares two catastrophic floods of 2024: in Valencia, Spain, and Porto Alegre, Brazil. In both cases, experts suggest that if more native vegetation hadn’t been lost to urban development and remained as it had in the past, the destructive force of these floods would have been significantly reduced. The piece also revisits the work of the late Spanish scientist Millán Millán Muñoz, former director of the Mediterranean Environmental Studies Center, who has long argued that deforestation profoundly affects hydrological cycles and rain patterns. His research suggests that when large forested areas are cleared, atmospheric humidity may become insufficient to generate rainfall. This, in turn, reduces precipitation, intensifies soil aridity and desertification, and increases vulnerability to flash floods.

Millán was invited by the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to contribute to its Third Assessment Report in 2002 but quit soon after, frustrated that his results were consistently questioned. According to Mongabay, Millán’s theory — which links human-driven factors, such as intensive agriculture and resource extraction, to climate disruption — was not politically well-received. Simpler, more easily measurable models were prioritized instead.

Like Millán, many scientists today criticize what they call a carbon dioxide-centric approach to climate action that focuses almost exclusively on carbon levels and their reduction as the primary strategy. While carbon dioxide is a critical factor, the climate crisis is fuelled by a complex web of interconnected drivers, including changes in land-use, that demand a broader perspective and actions on different fronts.

Wild horses as firefighters. That pastoralism in forested landscapes can help prevent wildfires has been discussed in previous editions of Lapilli. Sheep and goats have shaped the Mediterranean landscape for millennia. But in Galicia, Spain, a University of A Coruña researcher highlights the crucial role of the region’s estimated 11,000 wild horses in reducing flammable vegetation.

Wild horses have roamed Galicia for thousands of years and their presence plays a vital ecological role. By grazing, they help reduce highly combustible plants like gorse and make room for heather — particularly the Calluna vulgaris (common heather), which thrives near peat bogs and effectively captures carbon. The impact of these animals, researchers suggest, is a natural and effective form of wildfire prevention.

However, in recent decades, eucalyptus plantations, which now cover 28 percent of Galicia’s total forested area, have expanded due to incentives from the industrial pulp industry. These fast-growing, highly flammable trees have fuelled devastating wildfires during dry spells, especially when combined with strong Atlantic winds (Al Jazeera).

The forest that keeps Venice afloat. While concrete buildings along the Mediterranean coast are suffering from rapid erosion, Venice’s palazzi remain standing — supported by an ancient, hidden forest beneath the city. No one knows exactly how many millions of wooden piles support Venice, but beneath St. Mark’s Basilica, which was built in 832 AD, there are at least 10,000 oak trunks. These trees — mostly sourced from Cadore, an area in the eastern Alps — form the foundation of the floating city.

A BBC report explores the 1,600-year-old system that has kept Venice standing, including the rhythmic songs of the battipali (labourers who once drove these wooden piles deep into the lagoon’s muddy seabed). Their repetitive, methodical work endures to this day as a testament to an engineering marvel that has defied time.

The fragility of Alexandria. Alexander Durie, a cohort member of our Magmatic School of Environmental Journalism, has written a story for The Guardian with journalist Heba Khamis, documenting the growing environmental threats to Alexandria, Egypt — a city on the frontline of rising sea levels.

Despite being one of the most at-risk cities for coastal flooding, Alexandria residents do not yet feel an urgent need to move away. In recent years, the city has lost 40 percent of its beaches due to sea level rise, urban expansion and the privatization of shoreline areas. According to a recent study, hundreds of buildings have already collapsed as a result of coastal erosion, increased seawater intrusion and ground subsidence.

Yet, despite these visible changes, many residents in this city, which has been shaped by millennia of earthquakes and tsunamis, do not perceive this as an active threat to their daily lives.

Lithium mining vs small-scale farming. Natalie Donback, another fellow of our environmental journalism program, has published her investigative work on Context, Reuters’ environmental news platform. Her report sheds light on a growing conflict in Extremadura, a region in western Spain, where plans to mine lithium — a crucial mineral for the green transition — clash with efforts to preserve the landscape and promote small-scale agriculture.

Supporters of lithium extraction argue that it will create jobs and boost the local economy, while opponents question the long-term impact of mining on the environment and rural livelihoods. As the demand for lithium surges, Extremadura finds itself at a crossroads, forced to weigh economic opportunity against the preservation of its natural heritage.

The environmental impact of white phosphorus in Lebanon. Despite being banned as a chemical weapon under international law, white phosphorus continues to be used in military operations worldwide. One of the most recent uses of this toxic substance has been in attacks conducted by the Israeli military on Lebanon. An investigation by the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) examines not only the direct loss of human life but also the contamination caused by Israel’s use of white phosphorus and depleted uranium on Lebanese farmland, agricultural fields and water reservoirs.

White phosphorus is a wax-like substance, which is white or yellowish in appearance, that ignites spontaneously above 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit). The resulting fire cannot be extinguished with water and is highly toxic (likely lethal with only 10 percent of the body exposed), with devastating consequences also for the environment.

Studies have found alarmingly high levels of lead and cadmium in the Litani River, which is Lebanon’s longest waterway and crucial for both agriculture and urban water supply. The attacks have also wiped out oak, juniper and olive trees, says environmental engineer Hanna Mikhaiel in an interview with ARIJ — a loss that will only accelerate Lebanon’s ongoing desertification.

Slopes without snow. What will skiing in the Alps look like in 50 years? An investigation published on Irpimedia reports that, despite growing uncertainties about the industry’s future, investment in ski resorts continues. Projections suggest that in just 25 years, snowfall below 1,800 metres (5,905 feet) will all but disappear due to rapidly rising temperatures, leaving much of the sport reliant on artificial snow.

DAVIDE MANCINI

As a freelance journalist, he writes, photographs and films the changes that are affecting the Mediterranean region, with a focus on the environment. He has published several investigations with international media on issues such as forest fires, illegal fishing and sea pollution. Here is a link to his published work.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in May or earlier with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma.