In this Lapilli, we focus on persistent drought conditions that have pushed farmers to resort to prayers and religious processions to bring rain. We then look up into the sky and see that in recent weeks, especially in some parts of the Med, from Greece to Malta and Portugal, it has been covered by Saharan dust, a phenomenon that apparently is happening with more frequency and intensity. The effect of climate change on glaciers has become a tourist attraction in the French Alps, raising all sorts of questions. As a project in the Canary Islands does, which aims to farm octopus in industry-like buildings. This, and much more in this Lapilli. We hope you’ll enjoy it and spread it around! Happy reading!

Saints and water. Last month we focused on the drought conditions affecting Morocco and Italy’s main islands, Sardinia and Sicily. Thirty days later, the situation has slightly improved, but drought conditions persist across the Med. In some of the hardest-hit areas, people are willing to try anything to make it stop. In the city of Perpignan, in the French region of Catalonia, farmers have revived the ancient tradition of praying to their local saint, namely Saint-Gaudérique, and asking him to make it rain. The area is facing its worst drought since 1959, with groundwater levels worryingly low. In winter months, it rained 60 percent less than usual. According to old legends, Saint Galdric is able to make miracles, specifically make it rain. Indeed, after the procession it rained quite a bit, but not even close to heal the region from its thirst for water (Le Monde).

On the topic of religion, saints, and drought, we invite you to have a look at these beautiful photos of a religious procession from Quesada in Andalusia, where after years of drought, during Easter week, it finally rained (Associated Press). And it also rained in the Spanish region of Catalonia, where measures that restrict water usage are causing tension between farmers and tourism operators (Euronews).

Also, in Sicily drought conditions have not been improving much, with important repercussions on citrus production (Le Monde). And no saint is helping. The local government has announced a drought emergency until the end of the year, implementing measures to preserve water. The region’s water supply company has reduced the amount of water pumped into the system, and everyone is trying to figure out what to do during the notoriously hot Sicilian summer. This is not the first time the island has been affected by a drought, but this one is particularly long. Actually, in 2023, Sicily did receive a fair amount of rain, but it was mostly concentrated in two intense storms, one in May and one in September. Rain that comes suddenly and in great quantity is difficult to capture and doesn’t get absorbed by the soil. It mostly runs off to sea, evaporates quickly, or fills water reservoirs with mud, reducing their capacity (Il Post).

In the Italian Alps, however, thanks to heavy snowfalls in February and March, the snow deficit has been replenished, according to the CIMA Research Foundation. A surplus was even registered for the first time in two years. This means there is plenty of water stored in the form of snow for the months ahead. But along the Apennines and in the southern regions, the snow deficit is still significant.

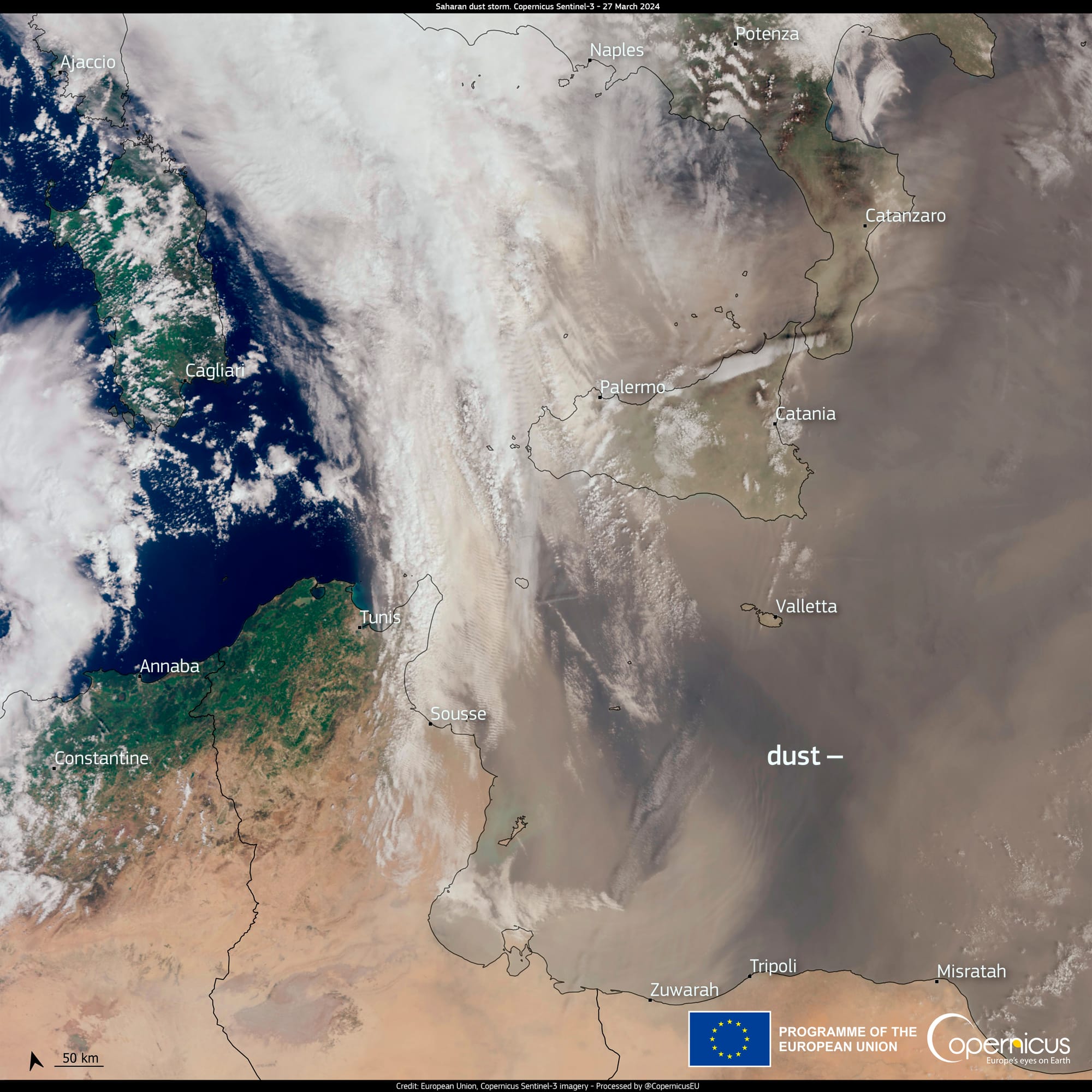

Dusty skies. In the last few days, dust from the Sahara has clouded the skies of several Mediterranean countries, in particular Malta, Greece and the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal’s Directorate-General of Health issued an air quality warning and recommended limiting time outdoors. Strong winds forming over the desert can blow the dust to very far places, sometimes even reaching the Caribbean, Latin America or Finland. The dust is rich in nutrients and minerals and helps phytoplankton grow in the ocean. When the dust travels very high up in the atmosphere, it creates spectacular sunsets, but when the dust hits areas closer to the desert, like the Mediterranean basin or the Canary Islands, it can lower air quality and pose a health risk. Last year, a group of Spanish researchers published a paper that shows how the frequency and intensity of these kinds of phenomena over the Western Mediterranean and Euro-Atlantic region seem to be increasing during the winter season, possibly due to changes in atmospheric circulation patterns (The Independent; Il Post).

Climate risk affects Europe’s north-south divide. According to the first European Climate Risk Assessment by the European Environmental Agency (EEA), climate change is exacerbating Europe’s north-south economic divide. Countries like Italy, Spain, Greece and Portugal, which are the most affected by droughts and extreme heat, are also the ones with the highest public debts and thus limited spending capacities to invest in adaptation and mitigation. The EEA highlights that regions with lower economic status, such as parts of Croatia, Greece, Italy and Spain, are particularly vulnerable to rising temperatures that impact wildfires, agricultural yields, water availability, human health and unemployment. The poorer these regions become, the less resources they have to cope with such emerging threats. The report also highlights how Europe as a whole lags behind in effectively responding to climate change's growing challenges, lacking cohesive policies and implementation plans to keep up with the pace of the unfolding climate crisis (Eunews; Politico.eu).

Rice’s uncertain future. The Po Valley accounts for half of Europe's rice production, largely due to its abundant water supply, which is crucial for rice cultivation. However, recent years have seen this important resource become scarce. Increasing temperatures and droughts are impacting both the crop yield and the economic and environmental sustainability of rice farming in the region. In 2022, the area faced its most severe drought in two centuries, leading to fields turning dry and brown by May instead of their usual vibrant green, as observed by farmers like Luigi Ferraris. Presently, efforts are underway to cultivate rice varieties that are more drought-resistant, but the future remains uncertain (The Guardian).

The tourism of climate change. This long reportage takes us to the Mer de Glace, the largest glacier in the French Alps, which has been dramatically receding due to rising temperatures. Over the years, it has attracted tourists seeking to see firsthand the effects of climate change. But the irony is that to allow more tourists to visit, new infrastructure is being built, generating fears that their environmental impact could actually contribute to climate change and the glacier's degradation (The New York Times).

Should we farm octopus? A project in the Canary Islands, Spain, is looking to set up an intensive farm, resembling a factory, to grow octopuses. It would work this way: The octopuses would be kept in small cages stacked atop each other in a multistory industrial building. Then, to kill them, they would be placed in ice water at minus 3 degrees Celsius (27 degrees Fahrenheit). Questions are being raised about whether this is the best way to feed on what is ultimately a highly intelligent being. Supporters argue that this could save octopuses in the wild that are being caught at increasing rates, but the idea of growing sentient animals, not only octopuses — think of pigs and others — solely for the protein-rich meat doesn’t seem like the most ethical and sustainable way to live on our planet (Yale Environment 360).

Shifting wine regions. A recent review delves into how rising temperatures are affecting wine cultivation around the world and predicts that many areas where wine is produced won’t be suitable for this kind of production in the future. According to the article published in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, “about 90 percent of traditional wine regions in coastal and lowland regions of Spain, Italy, Greece and southern California could be at risk of disappearing by the end of the century because of excessive drought and more frequent heat waves with climate change.” On the other hand, depending on how much the temperature rises, new suitable regions may emerge in northern France as well as upslope, potentially raising conflict centered around the environmental protection of natural areas.

Dry stone walls. In the latest issue of Lapilli+, our premium newsletter with original content, we brought you to the protected and rich-in-water valley of Niasca, on Mount Portofino, Italy. Here, a group of people is fighting rural depopulation by restoring the historical landscape made of terraces and dry stone walls that help collect water. “As we delved deeper into the project, the concept of seeking and harnessing water became somewhat of an obsession for us,” says architect Antonio Marruffi, who is overseeing the project's implementation. If you missed it, you can switch to Lapilli Premium and find the full story here.

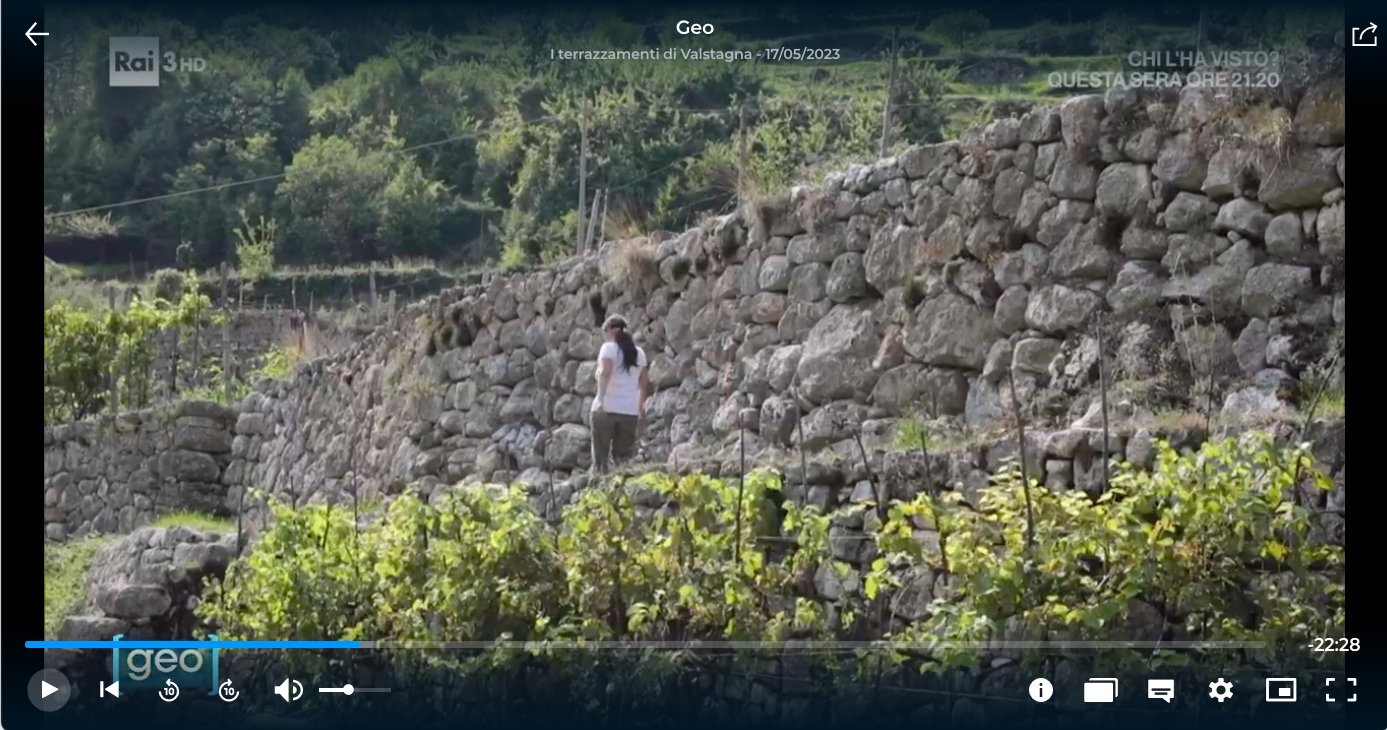

And speaking of dry stone walls, here is a very interesting episode of Geo, a TV program from the Italian public broadcaster RAI. For this documentary, their journalists visited Valstagna, a little village in the mountains close to Vicenza, where terraces made with dry stone walls had once been used to cultivate tobacco from the 17th century to the 1960s. The tradition has since faded away, but a few tobacco farmers still exist. And community efforts are underway to preserve dry stone walls and terraces that, without human presence, inevitably tumble away or get swallowed by trees (Raiplay from minute 2:15:55).

GUGLIELMO MATTIOLI

As a multimedia producer, he has contributed to innovative projects using virtual reality, photogrammetry, and live video for The New York Times. In a past life, he was an architect and an urban planner, and many of the stories he produces today are about the built environment and design. He has worked with publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, and National Geographic. He has been living and working in New York City for 10 years.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in May or earlier with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma. Here you can read Magma's manifesto.