In this issue of Lapilli, we focus on the Valencia floods aftermath, highlighting a photo-reportage that centers on some of the survivors. Since this is the season for olive harvesting, one of the quintessential fruits of the Mediterranean, we bring you two very different stories — one from Lebanon and one from Spain — tied to this traditional crop.

We also discuss the latest report by the Mediterranean experts on climate and environmental change (MedECC) and a study mapping the areas in the world with the highest risks of collisions between large ships and whales. Finally, we show you what the Swiss landscape might look like in 2075 if measures to contain global warming are only moderately effective.

As always, we hope you enjoy this newsletter. If so, feel free to forward and share it.

This is the last issue of Lapilli for this year, but we’re already working on new projects and stories for 2025! (The last Lapilli+ is coming in two weeks.)

Thank you for reading and staying with us throughout 2024, a year filled with Mediterranean climate stories and events.

Heavy rains flood displaced Palestinians. In late November, rainstorms affected different parts of Gaza where those displaced by the conflict between Israel and Hamas are living in tents. Flooding has contributed to making living conditions even more difficult. Among the consequences of the rainfalls is an increase in the price of the plastic sheets used to keep belongings and people dry (Reuters; Al Jazeera).

Storm hits Greece. Storm Bora battered eastern Greece with heavy rains and gale-force winds during the last weekend of November. Thirty centimeters (nearly 12 inches) of rain fell on Rhodes over 16 hours, flooding roads and isolating some villages. The mayor has requested the government declare a state of emergency for the island. Further north, two people died on the island of Lemnos; in Thessaloniki there was severe disruption due to high winds (Kathimerini; BBC).

Torrential rains in Sicily yet drought conditions continue. Italy also experienced intense weather events in November. On the eastern coast of Sicily, the streets once again turned into rivers in towns, including Giarre, Acireale and Catania (as had already happened in October). On the island of Stromboli, where a devastating fire occurred in 2022 increasing hydrogeological risk, mud and sand now flood the narrow streets every time there is heavy rain, including in recent weeks. Residents are now calling for more action to protect against the next major flood (Il Post).

Despite these recent rainfalls, though, the water crisis continues to affect the region, especially in central Sicily, where reservoirs are struggling to replenish. In Palermo, water rationing currently affects 250,000 inhabitants, which is roughly 40 percent of the city’s population (Ansa).

A water-rich district runs out of water. About 230 miles north east, in Basilicata, water is also scarce. The area is rich in spring water but has the highest rate of water loss in Italy. According to Italy’s National Institute of Statistics, 65 percent of the water in Basilicata's network is wasted due to old pipelines and poor maintenance. Low levels of rainfall and snowfall have also exacerbated the current crisis, contributing to the drying up of Lake Camastra — an artificial reservoir that supplies water to Potenza and the surrounding area.

Since late September, water levels have been so low that rationing measures were implemented. This has sparked debates among various agencies and political parties over who is responsible for such a critical situation in a district so abundant in water. Meanwhile, at the end of November, Civil Protection, a governmental agency, deployed three pumps to temporarily draw water from the Basento River, though many fear water quality issues (Avvenire, Il Post).

The Valencia floods aftermath. At the end of October, the Valencia region of Spain was hit by exceptional rainfall that caused severe flooding and resulted in the deaths of more than 200 people. In the weeks following the disaster, there was intense backlash against the local government for failing to adequately warn the population.

Immediately after the event, journalists and photographers from SONDA, a Spanish journalism nonprofit dedicated to visually documenting the climate crisis, visited the town of Paiporta, which was most affected by the flood. They collected and photographed the stories of residents who lost everything and narrowly survived that night, clinging to anything they could to avoid being swept away by the water (SONDA Internacional).

What happened in Valencia highlighted flaws in the warning system that extend beyond Spain. While Europe and the entire Mediterranean region are warming faster than other parts of the world, leading to increasingly intense weather events, some countries have yet to implement reliable and effective early warning systems.

In the Spanish case, there was a lack of coordination between the national meteorological agency, which had predicted the event, and the local government, which only sent an alert to residents' phones at 8 p.m., when the situation had already become critical.

A similar issue occurred during the floods in Germany and Belgium in 2021. Experts attribute this to poor coordination among the agencies responsible for weather monitoring and a lack of public education on emergency preparedness, as many citizens are unsure of what to do when they receive an alert (Context).

Olive harvest amid the war. For many Mediterranean countries, November is the time for harvesting and pressing olives to make oil, including in the war-torn Middle East. This story, written before Israel-Hezbollah ceasefire deal, and accompanied by stunning photographs, takes us to southern Lebanon, in the village of Kaukaba, where, despite Israeli bombings, people gathered to harvest olives as they have done for millennia (NZZ).

In the West Bank, instead, tensions between Palestinian farmers and Israeli settlers are at their peak. To understand what is happening, we highlight two stories: the first is about acts of violence committed by Israeli settlers against Palestinian farmers; the second tells how a Palestinian woman was killed by Israeli soldiers while picking olives in Jenin (The New Arab).

“Made in Italy” oil uses olives from Spain. Italy produces only 10 percent of the world's olive oil yet it is one of the largest exporters globally. This is made possible – not from Italian olives — thanks to olives grown in Spain, Tunisia, Greece, Portugal, Türkiye and Syria, which comprise the majority of the olive oil that Italy exports. Meanwhile, Spain produces about 40 percent of the world’s olive oil but struggles to establish itself as a direct exporter.

The reasons behind this curious role reversal, the commercial strategies involved and how things are changing can be found in a detailed piece published in El Orden Mundial. The explanation involves Franco-era policies, the post-World War II period and Italian emigration worldwide.

“Spain has done great work in increasing agricultural production,” says Rafael Gutiérrez, Chief Operating Officer of Dcoop, one of the world’s largest olive oil producers, based near Málaga, Spain, to El Orden Mundial. “While Italy has focused heavily on marketing.”

Climate coastal risks in the Mediterranean. In the month that just ended, the 29th Conference of the Parties (Cop29) to the United Nations Convention on Climate Change took place in Baku, Azerbaijan. To find out how it went we suggest diving deep into The Guardian’s coverage of the event. Here we simply recommend one of two reports on the future of the mare nostrum (our sea) that MedECC presented during Cop29.

In the report, experts highlight the risks for coastal areas across the region, which will increasingly face rising sea levels, threats to infrastructure and the potential displacement of 20 million people by 2100. Sea-level rise in fact leads to increased coastal erosion, flooding and the salinization of aquifers. Additionally, coastal zones will become more vulnerable to intense and overlapping weather events, such as storms, flash floods and high tides.

The report emphasizes the need to preserve coastal ecosystems by adopting measures to slow coastal erosion, manage invasive species and reduce plastic pollution as well as fossil fuel emissions.

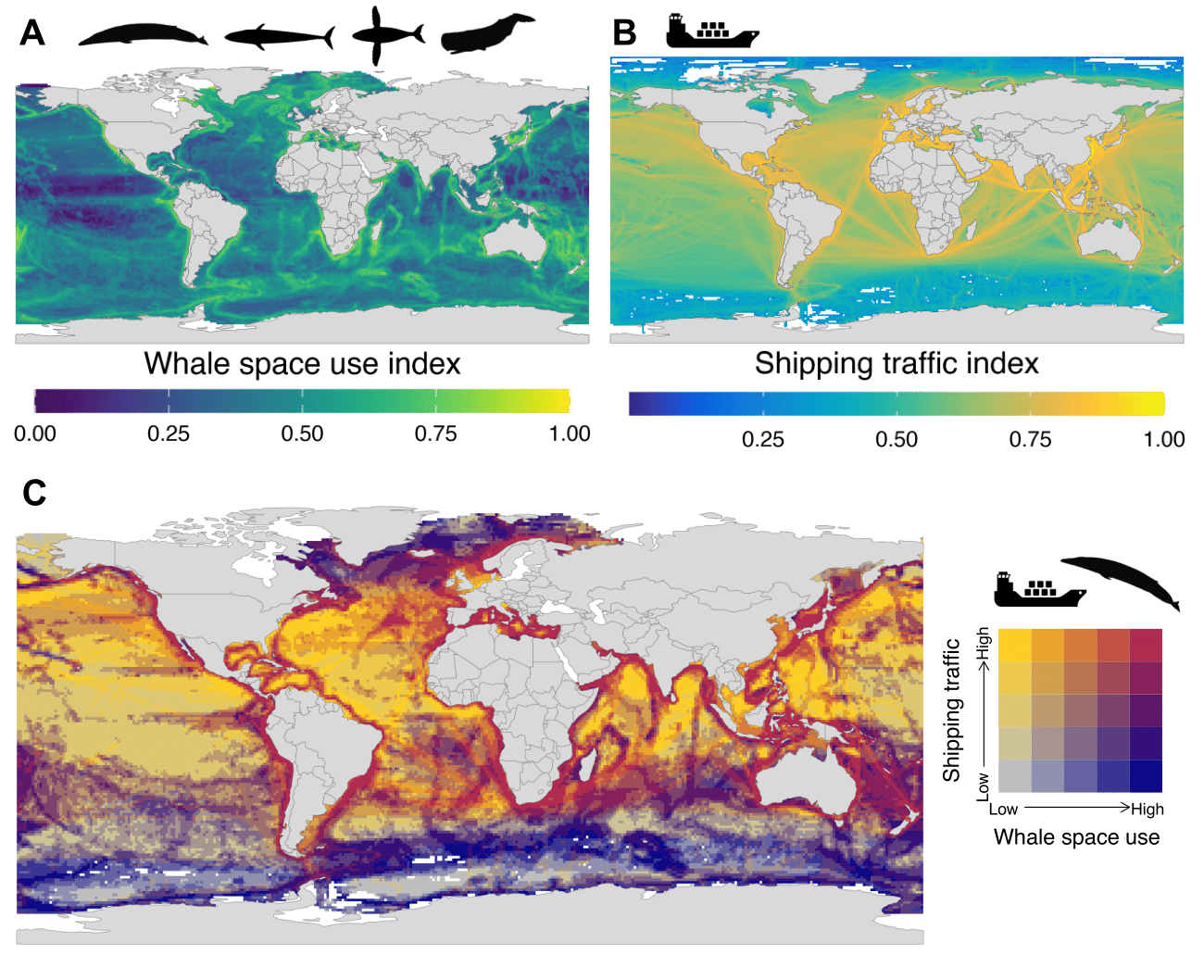

How to avoid whale strikes on ships. Researchers at the University of Washington, Tethys Research Institute in Italy and others recently published a study that quantified the risk of collisions between ships and large cetaceans globally in Science. The research focused on four of the most common and endangered species affected by maritime traffic: blue whales, fin whales, humpback whales and sperm whales. Collisions, in fact, are among the leading causes of death for most of these species.

Most marine traffic occurs in 92 percent of the areas where whales are most commonly found, but only 7 percent of these areas have strategies in place to prevent collisions.

One of the areas with highest risks is the Mediterranean Sea, one of the world's busiest bodies of water. The study highlights how simple low-cost interventions could significantly reduce the risk of collisions. These include activating warning systems to inform ships of the presence of whales that will allow them to reduce speed and altering ship routes slightly to avoid the areas most frequently visited by cetaceans (as has been done in the Ionian Sea off Greece to prevent collisions with local sperm whales).

Most of the areas where whales concentrate are within national borders, close to the coast, so individual countries could independently implement safety measures, avoiding the need for complex international treaties. The study also states that expanding anti-collision measures to an additional 2.6 percent of the ocean would protect the highest risk areas.

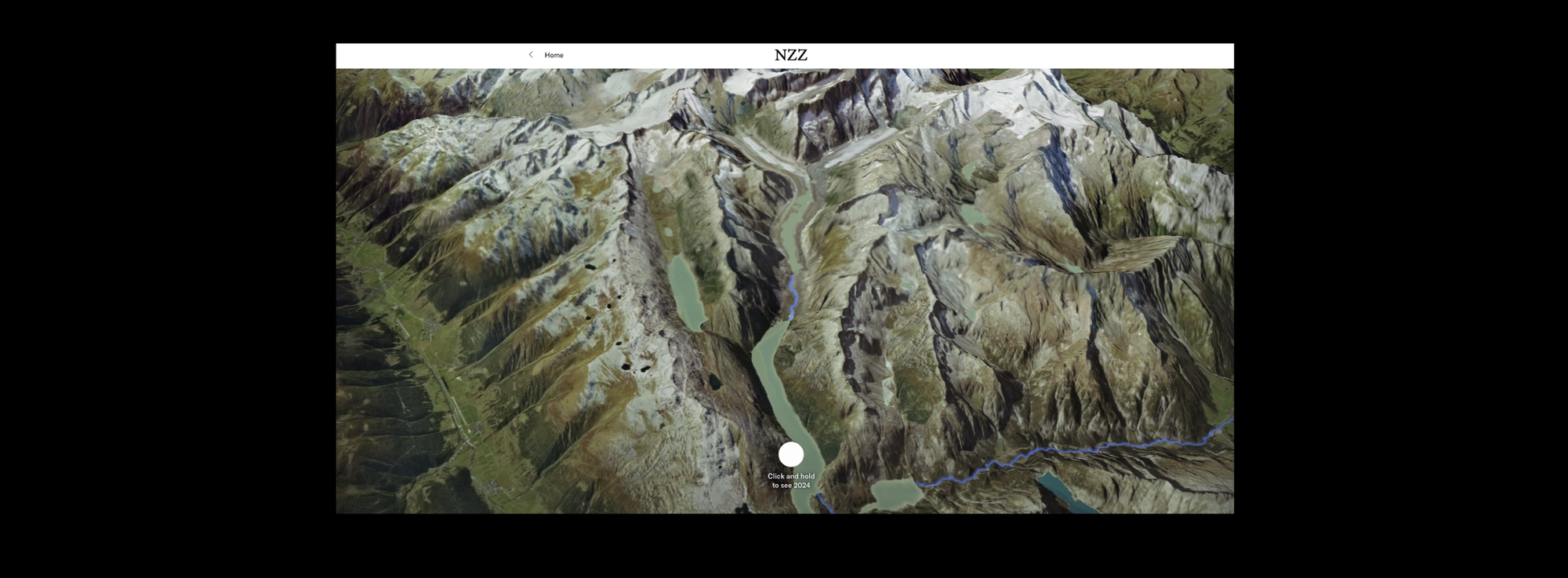

The Swiss landscape of 2075. Finally, we feature this interactive article in which the authors, following the course of the Aare River, which flows from the Bernese Alps into the Rhine, show what the Swiss landscape might look like in 2075 if measures to mitigate climate change are only moderately effective. According to the scientific projections underlying the graphics that accompany the piece, there will be no more glaciers, the perennial snow line will be higher, forests will grow at higher elevations and rivers will be warmer by 2075. The types of crops and plants will also change. In short, the Swiss landscape will be very different from how we know it (Nzz).

GUGLIELMO MATTIOLI

As a multimedia producer, he has contributed to innovative projects using virtual reality, photogrammetry, and live video for The New York Times. In a past life, he was an architect and an urban planner, and many of the stories he produces today are about the built environment. He has worked with publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, and National Geographic. He has been living and working in New York City for more than 10 years.That's it for this month. Thank you for reading this far. See you in January or earlier with Lapilli+.

If this newsletter was forwarded to you, you can subscribe here to continue receiving it. Lapilli is free and always will be, but in case you would like to buy us a coffee or make a small donation, you can do so here. Thank you!

Lapilli is the newsletter that collects monthly news and insights on the environment and the Mediterranean, seen in the media and selected by Magma.